For the hundreds of rural U.S. hospitals struggling to stay in business, health policy decisions made in Washington, D.C., this summer could make survival a lot tougher.

Since 2010, at least 79 rural hospitals have closed across the country, and nearly 700 more are at risk of closing. These hospitals serve a largely older, poorer and sicker population than most hospitals, making them particularly vulnerable to changes made to Medicaid funding.

"A lot of hospitals like [ours] could get hurt," says Kerry Noble, CEO of Pemiscot Memorial Health Systems, which runs the public hospital in Pemiscot County, one of the poorest in Missouri.

The GOP's American Health Care Act would cut Medicaid — the public insurance program for many low-income families, children and elderly Americans, as well as people with disabilities — by as much as $834 billion. The Congressional Budget Office has said that would result in 23 million more people being uninsured in the next 10 years. Even more could lose coverage under the budget proposed by President Trump, which suggests an additional $610 billion in cuts to the program.

That is a problem for small rural hospitals like Pemiscot Memorial, which depend on Medicaid. The hospital serves an agricultural county that ranks worst in Missouri for most health indicators, including premature deaths, quality of life and even adult smoking rates. Closing the county's hospital could make those much worse.

And a rural hospital closure goes beyond people losing health care. Jobs, property values and even schools can suffer. Pemiscot County already has the state's highest unemployment rate. Losing the hospital would mean losing the county's largest employer.

"It would be devastating economically," Noble says. "Our annual payrolls are around $20 million a year."

All of that weighs on Noble's mind when he ponders the hospital's future. Pemiscot's story is a lesson in how decisions made by state and federal lawmakers have put these small hospitals on the edge of collapse.

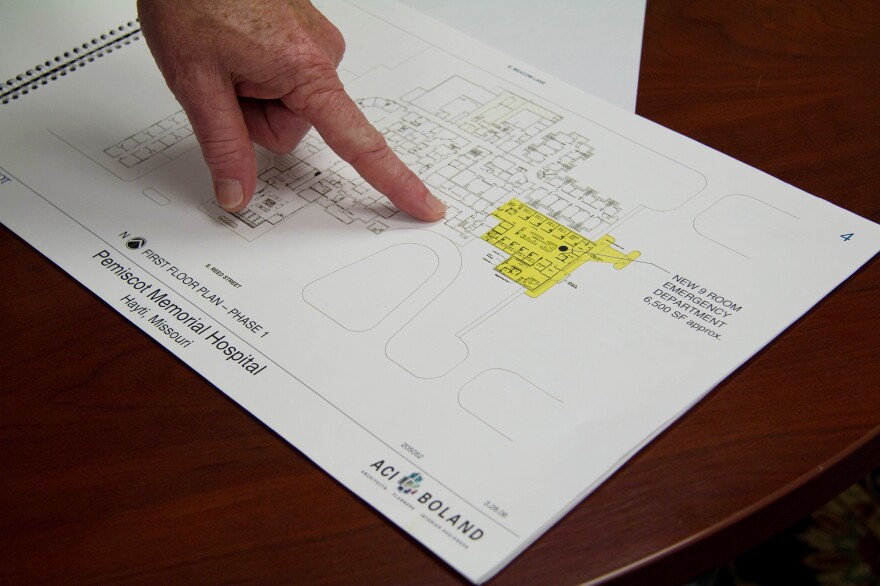

Back in 2005, things were very different. The hospital was doing well, and Noble commissioned a $16 million plan to completely overhaul the facility, which was built in 1951.

"We were going to pay for the first phase of that in cash. We didn't even need to borrow any money for it," Noble says while thumbing through the old blueprints in his office at the hospital.

But those renovations never happened. In 2005, the Missouri legislature passed sweeping cuts to Medicaid. More than 100,000 Missourians lost their health coverage, and this had an immediate impact on Pemiscot Memorial's bottom line. About 40 percent of their patients were enrolled in Medicaid at the time, and nearly half of them lost their insurance in the cuts.

Those now-uninsured patients still needed care, though, and as a public hospital, Pemiscot Memorial had to take them in.

"So we're still providing care, but we're no longer being compensated," Noble says.

And as the cost of treating the uninsured went up, the hospital's already slim margins shrunk. The hospital went into survival mode.

The Affordable Care Act was supposed to help with the problem of uncompensated care. It offered rural hospitals a potential lifeline by giving states the option to expand Medicaid to a larger segment of their populations. In Missouri, that would have covered about 300,000 people.

"It was the fundamental building block [of the ACA] that was supposed to cover low-income Americans," says Sidney Watson, a St. Louis University health law professor.

In Missouri, Kerry Noble and Pemiscot Memorial became the poster children for Medicaid expansion. In 2013, Noble went to the state capital to make the case for expansion on behalf of the hospital.

"Our facility will no longer be in existence if this expansion does not occur," Noble told a crowd at a press conference.

"Medicaid cuts are always hard to rural hospitals," Watson says. "People have less employer-sponsored coverage in rural areas and people are relying more on Medicaid and on Medicare."

But the Missouri legislature voted against expansion.

For now, the doors of Pemiscot Memorial are still open. The hospital has cut some costly programs — like obstetrics — outsourced its ambulance service and has skipped upgrades.

"People might look at us and say, 'See, you didn't need Medicaid expansion. You're still there,' " Noble says. "But how long are we going to be here if we don't get some relief?"

Relief for rural hospitals is not what is being debated in Washington right now. Under the GOP House plan, even states like Missouri that did not expand Medicaid could see tens of thousands of residents losing their Medicaid coverage.

This story is part of NPR's reporting partnership with KBIA, Side Effects Public Media and Kaiser Health News. The local version also got support from the Association of Health Care Journalists and The Commonwealth Fund.

Copyright 2020 KBIA. To see more, visit KBIA. 9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))