Jimmie Childress had been sitting in a Kansas City jail for two months, waiting to be tried for transporting stolen property across state lines. It was the spring of 1967, and Jimmie was 18 years old. When he finally walked into a courtroom for his hearing, the judge gave him an ultimatum.

"Either go into the military or go to prison. Which is it going to be?"

Childress was tired of being locked up. "So naturally, I chose going into the military."

Childress was trained to be a paratrooper and was assigned to the 101st Airborne Division. He landed in Vietnam in November 1967. "I knew nothing about the war, I knew nothing about Vietnam," he said.

Just a year earlier, Jimmie's criminal history might have been made him ineligible for the armed forces. But in August 1966, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara announced "Project 100,000," an initiative that was intended to simultaneously lift men out of poverty and provide troops for the war in Vietnam. Between 1966 and 1971, Project 100,000 sent more than 400,000 men to combat units in Vietnam - 40 percent of them, like Jimmie Childress, were African American.

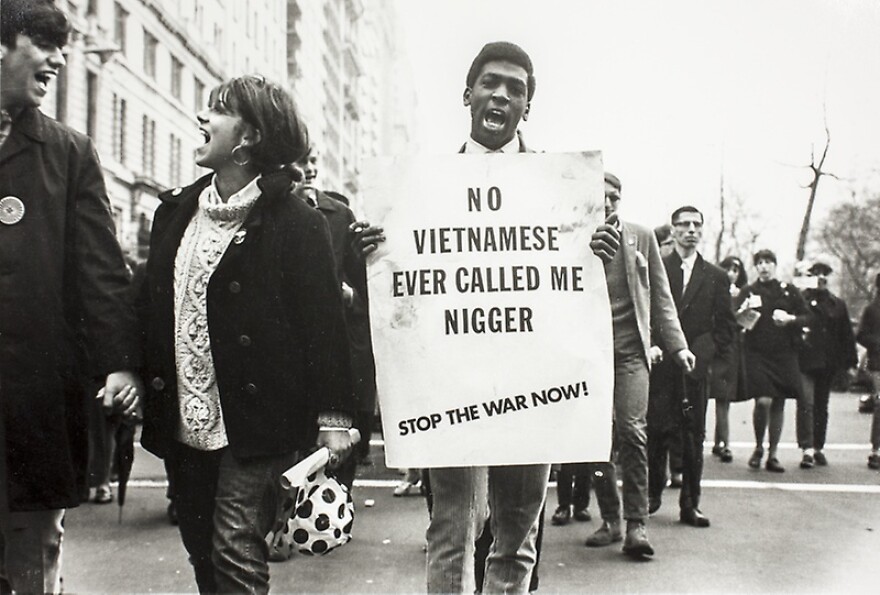

The Vietnam war was the first completely integrated American war. Only two decades earlier, during WWII, black and white troops were segregated. At the beginning of the Vietnam conflict, African American troops re-enlisted nearly four times more than whites. Many black people volunteered to fight in dangerous combat units, which received higher pay. But by 1967, African American leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Stokely Carmichael were speaking out against the war.

As the war dragged on and casualties piled up, the mood among troops stationed in Vietnam soured. Black reenlistment rates plunged from 66.5 percent in 1967 to 31.7 percent in 1968. Black soldiers spoke openly about the discrimination they felt within the military, and racial tensions between black and white troops.

Wallace Terry, an African American journalist for Time magazine, recorded black GIs talking about how southern white soldiers were allowed fly the confederate flag, while black soldiers were reprimanded for displaying symbols of the black power movement.

In 1968, there were half a million troops in Vietnam, a quarter of them drafted to fight. As discontent with the war grew, discipline started to fray. More and more soldiers were rebelling by going AWOL (Absent Without Leave).

Jimmie Childress was one of them. After months of fierce combat, he got disillusioned with the war, and decided to quit fighting. He disappeared from his unit with a group of other black soldiers and lived for months underground, staying with Vietnamese peasants in the countryside and hiding out in Saigon's "Soul Alley," a neighborhood where many black GIs congregated in their off hours. "During that time, I was stealing from the military M-16s, grenade launchers, I even stole a couple jeeps," he told Radio Diaries. He then sold these items on the black market to make money.

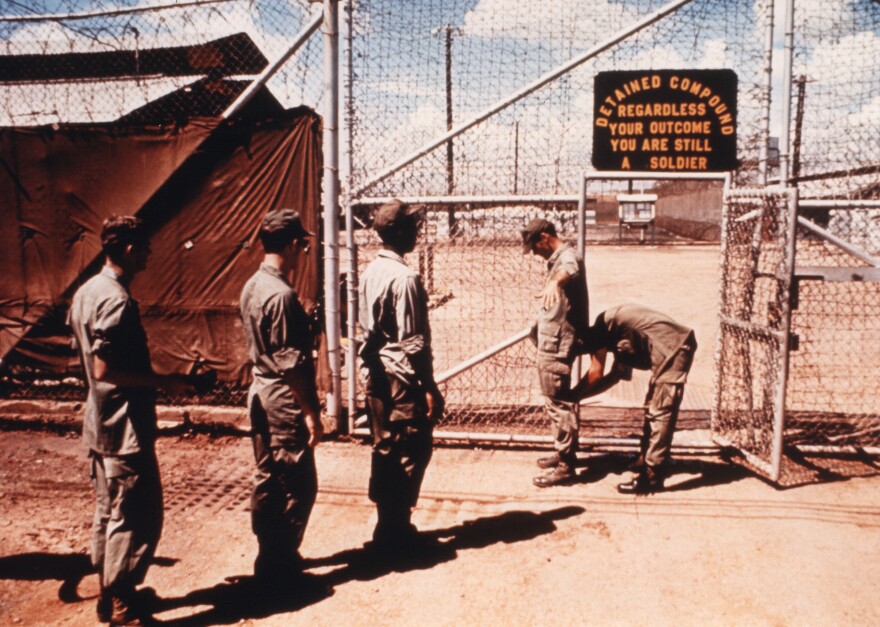

Eventually, he was caught and sent to the army's notorious Long Binh Jail - LBJ for short - on the outskirts of Saigon. This military stockade held American soldiers who were serving short sentences before being sent back to the field, as well as soldiers who had been convicted of serious crimes who were waiting to be shipped back to jail in the United States.

The reasons soldiers were serving time at LBJ varied greatly. Some were there for serious crimes, like murder. Others were there for small infractions, such as refusing a direct order to get a haircut. By the summer of 1968, over half were being held on AWOL charges.

Originally built to house 400 inmates, in August of 1968, LBJ was crammed with 719 men. And - in a mirror of the U.S. justice system - black soldiers were greatly overrepresented in the jail. Despite representing 11% of the troops in Vietnam, more than 50% of the men incarcerated at the stockade were black. Many black soldiers felt they were more severely punished than white soldiers for similar offenses.

Conditions at LBJ were notoriously harsh. "Long Binh [Jail] was the kind of place that from the moment you walked in, you were trying to figure out a way to get out. Here you are in a war zone, in a jail, just at their mercy," remembers Scott Riley, another black soldier who sent to the stockade after getting caught with "a whole lot of marijuana."

Former inmates cite mistreatment by guards, particularly in solitary confinement. The military rehabbed shipping containers as jail cells. "The temperature in the box was 100+ degrees, the light was constantly on, 24 hours a day, and you were in there, naked," remembers Riley.

As LBJ grew more crowded, tensions along racial lines deepened. "Black and white being in Vietnam was no different than black and white being in America," said Childress. Richard Perdomo, a white inmate, remembers stark self-segregation among the inmate population. "We weren't separated by the military, we were separated by the want to be separated."

Radio Diaries spoke with the Deputy Commander of the stockade, an African American officer, who would only talk on the condition of anonymity. "There's always tension between races in a prison. You can control this with adequate staff. When you have control, the tension becomes dormant." According to him, a major problem was that the number of guards had not kept apace with the inmate population explosion. "We needed more people. None came," he said.

Simultaneously, news was trickling into the prison about the turbulent events in 1968 in the United States. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. was a turning point for many black soldiers in Vietnam. "A new burst of anger was afoot in the prison," said Riley.

Sitting in LBJ, Jimmie Childress could no longer ignore the irony of putting his life on the line for a country where African Americans still faced deep racism. "Why am I even over here? When you can't even go back to America and sit a lunch counter, you know?" He and other black soldiers felt that their real fight was in America, not Vietnam.

Frustrated about being in Vietnam, and angry about their treatment in the stockade, Childress and many other black soldiers in the prison had reached a breaking point. "We were hot, and crazy, we were fed up. So we decided, we're going to tear this M***F*** down."

Close to midnight on August 29, 1968, a group of inmates overpowered the guards, and with homemade weapons and bare hands, started tearing down the stockade.

Childress set his sights on the administrative building, where all the records of the incarcerated soldiers were kept. He and a few other inmates kicked the door in and started lighting papers on fire. "I figured the records were the key to causing more confusion for the military," he said.

Scott Riley was locked up in solitary confinement on the night of the riot. "Out of nowhere, this black guy opens the door and says, 'come on out man.'" The man then handed Riley a piece of cake that had been liberated from the kitchen. "The euphoria of being free, that moment was a beautiful moment. Knowing all the while that this is not going to end well."

Meanwhile, the guards at the stockade were terrified. "Everything just sped up in fast motion. I saw 6-8 prisoners running toward me. They threw me to the ground, started kicking and pummeled me with fists," said Larry Kimbrough, who was on duty that night.

The deputy commander, the highest ranking black officer at the stockade, entered the melee to try to diffuse the riot. "I was surrounded by about 100 inmates. I think I talked to them for a good 15-20 minutes. But then I heard two or three of them saying, 'you outta kill the Uncle Tom.' They stopped listening to what I was saying so I left. They opened the gate for me and let me out."

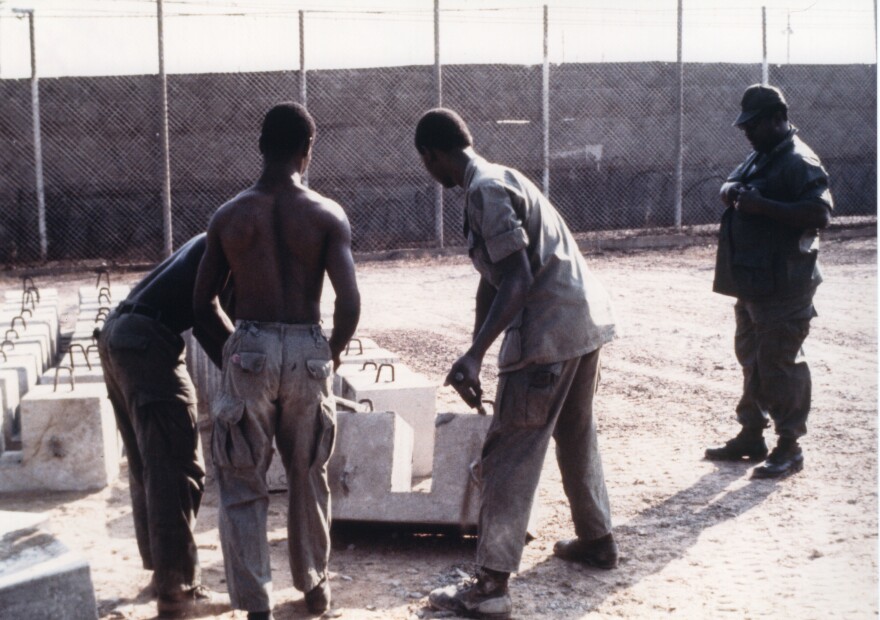

The riot escalated. A white inmate, Richard Perdomo, said it devolved into a frightening chaos. "Everybody went to fighting everybody. People were just knocking each other in the head, starting fights, swinging shovels and picks and stuff. It wasn't just blacks on whites, it was everybody, just lashing out," he said. "It was the only time I was ever scared the whole time I was in Vietnam."

By the early morning hours of August 30, 65 soldiers were injured, and one white inmate had been killed, Edward Oday Haskett. He was struck in the head with shovel by a black inmate. Much of the stockade had been torn down, including seven buildings and 19 tents. The stockade commander, Vernon D. Johnson, had also been severely beaten.

The military told reporters that the riot had been suppressed and order was restored. But that wasn't the whole story. Three weeks later, the military revealed to reporters that 12 black soldiers still controlled a section of the stockade.

"The military was literally throwing boxes of C-rations over the fence for us to eat. So we kind of knew they weren't going to kill us. People started pulling out drugs from god only knows where, and we're literally laying in the yard in the hot sun getting high," remembers Riley.

Peter Arnett covered the story for the Associated Press. "At any point the military could have overwhelmed this group of resisting black prisoners. The decisions were made not to do it. The high command realized the story could grow much bigger. And with the resistance to the war growing, they just didn't want to start drawing even greater attention to this whole racial issue in Vietnam," Arnett concluded.

At the end of September the military sent in a company of armed Military Police with tear gas in a riot control formation. That brought a decisive end to the riot at LBJ. The military did a thorough investigation and wrote a report about the riot. They concluded that the cause lay in racial tensions, along with overcrowding and understaffing. The ringleaders were charged with a litany of charges including murder for the man who was killed, assault and arson. The stockade was rebuilt, and a new commander was brought in, Ivan Nelson, nicknamed "Ivan the Terrible," who maintained strict discipline at the stockade.

"After the riot, I felt bad about it. I had regrets," said Childress. "And I felt disappointed because we didn't accomplish anything, other than tearing something up. Like a child would tear up a toy. We just blew off steam. And we only made our bed harder than it was before."

LBJ continued to house American soldiers until 1973, when American troops left Vietnam. At that point it was transferred to the Vietnamese government, which converted it into a drug treatment facility. The area where the stockade stood is now a manufacturing center.

The story of the uprising made a few headlines, but was largely overshadowed by other news in 1968. It doesn't appear in most history books about the Vietnam war. The people interviewed for this story are speaking publicly about the riot for the first time.

"It's not like describing a battle. There's nothing heroic about it. Families just don't like to think about their sons marching off to war, and instead of marching off to war, they march off into a stockade," said Perdomo.

The experience of being in jail in Vietnam continues to haunt Jimmie Childress. "I'm still angry about the way the military treated its own citizens. I still feel that something hand to be done," he said. "I guess I was just trying to prove that I was a human being. I'm over it now, but it took a long time. It took a long time."

This story was produced by Sarah Kate Kramer of Radio Diaries, with Joe Richman and Nellie Gilles. It was edited by Deborah George and Ben Shapiro. You can hear more Radio Diaries stories on their podcast. Thanks to Gerald F. Goodwin, whose New York Times op-ed led us to this story, and to historian Kimberley L. Phillips. Also thanks to David Zeiger of Displaced Films and and James Lewes of the GI Press Project for sharing their photographs with us of the LBJ. Lastly, thanks to Thomas Watson of the 720th MP Reunion Association and History Project for sharing the Military's CID Report.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.