Numbers drive baseball, a game whose managers, analysts and fans obsess over matchups, tendencies and results. Its box scores, those proto-spreadsheets, instantly turn human accomplishments into history. The quest is for clean, comparable data.

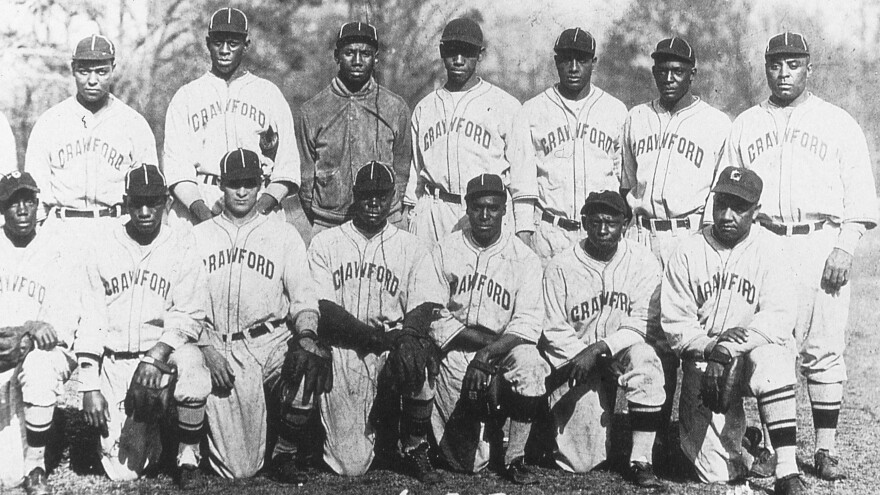

But for decades, the human aspect of the game — specifically, the racism that pro baseball both reflected and perpetuated — clouded that data. While the feats of white players were carefully recorded and celebrated, the accomplishments of Black players in the Negro Leagues were set apart or forgotten entirely.

But that's been changing: Baseball Reference, a gatekeeper of the game's statistics, is integrating data from the Negro Leagues era of 1920-1948 into its record books — a move it calls "long overdue."

"We are not bestowing a new status on these players or their accomplishments," Baseball Reference said. "The Negro Leagues have always been major leagues. We are changing our site's presentation to properly recognize this fact."

The change follows Major League Baseball's recent move to finally recognize the Negro Leagues, which has 35 players in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, as having "major league" status. In both cases, the shift was framed as the correction of an oversight. And that's how it should be, says Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo.

"The Negro League players themselves were never seeking validation from anyone," Kendrick tells NPR. "They knew how good they were; they knew how good their league was."

Integrating the players' statistics is no simple task. To get a sense of what the changes mean to baseball's history, NPR spoke to Kendrick after Baseball Reference announced its revised policy.

Note: This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

For so long, even the statistics from Black ball players were kept separate from the other major leagues. Does this feel like another remnant of segregation is finally falling?

Oh yeah. We look at it from the standpoint that Major League Baseball acknowledged what we already knew, that the Negro Leagues were a major league.

In some ways, we see it as a reckoning. And I think for me, that aspect of it means even more than the integration of the statistics into the annals of Major League Baseball history.

We're thrilled that Commissioner [Rob] Manfred and Major League Baseball did what could have and should have been a long time ago — and no one did it. He had the wherewithal to right a wrong. And that's exactly what he did. I tip my cap to him and all involved with pulling this effort together.

What we're seeing now is the impact of the decision made in December by MLB. It has a ripple effect that is all positive. Baseball Reference is regarded by many fans as the Bible. And it is — for those who want statistical data, that is the go-to source. Needless to say, we were thrilled to see Baseball Reference make their announcement.

People are celebrating Negro League statistics being incorporated into the record books. But we're also seeing that some big stars' numbers now look very different. Why is that?

You're going to get a smaller sample size. Because these statistics are going to focus solely on league games, and the Negro Leagues didn't play as many games in their season as Major League Baseball did. Most of the previous numbers looked at all levels of competition, including barnstorming games. And none of those games will be accounted for [in the new statistics].

I've got mixed emotions about that, to be honest. For me, I would have included every game that you could account for — I don't care who they were against. My position is that they didn't ask to play in the Negro Leagues; they had to play in the Negro Leagues. They had to play whoever they could play, whenever they could play. That includes even major league competition, where they played countless barnstorming games against each other. Those numbers won't be accounted for.

What are some examples of that?

Josh Gibson's home run totals won't sound as impressive as we all know them to be, because they're going to be focused strictly on league games. So now you have to delve into, 'OK, he hit a home run every X number of at-bats,' that kind of thing, to get a clearer picture of just how magnificent Josh Gibson really was.

But I tell people all the time: You can never reduce the story of the Negro Leagues to just statistics. It won't account for the circumstances in which they were playing these games. They were performing at such a high level under the most adverse set of circumstances.

Case in point, a pitcher like Satchel Paige. In 1943, J.L. Wilkinson bought an airplane and hired Paige out to pitch for other teams and then fly him back to pitch for the Kansas City Monarchs. The numbers are never going to tell you that — it's why I say they're contextual.

Numbers won't tell you the real story. Hopefully it whets your appetite and you want to learn more about these legends of the game to the point that you come visit the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and learn the greater story.

What else should happen for these players' history, and the Negro Leagues' history, to be preserved and put in their rightful place?

The historians have done a really good job — because none of this would be possible without them. They have done yeoman's duty to unearth what is now being utilized to quantify these numbers. That being said, do I think that there's even more out there? My guess is that there is. But we don't get to that historic day in December without the diligence, the commitment and the passion of those who have dedicated themselves to researching Negro Leagues history.

I'm not saying that it was like finding a needle in a haystack, but it damn near was. And these folks should be commended for the work that they did.

The exclusion of the Negro Leagues is linked to Major League Baseball's Special Baseball Records Committee, from the late 1960s. What did that committee do?

Well, they recognized all these other leagues but failed to recognize the Negro Leagues.

There are leagues that were acknowledged as major-league caliber, like the Federal League and others, and the committee blatantly dismissed the Negro Leagues. You know it was racially motivated, because we're talking about a league that was as good as any, and had more impact on Major League Baseball than any of the leagues that were recognized.

Many of the Negro League teams were renting the major league ballparks, and in most instances, they were filling up the ballpark. Major-league owners were making money off the Negro Leagues, getting a percentage of the gate and likely all of the concessions.

Then, after Jackie Robinson breaks the color barrier, this tremendous influx of talent moves into the major leagues. We're talking about the greatest influx of talent in any one single time frame in Major League Baseball history — and the majority of that talent came from the Negro Leagues, this league that was deemed somehow or another "less than."

You know it was racially motivated, and it had been that way since the late '60s. So that's why I say I tip my hat to Commissioner Manfred, because he did what others could have done — and they didn't.

Did the MLB think about forming a new special committee after the 1960s, to fix that?

It's really interesting. Most of us didn't even know about this commission until recently, when someone wrote about it. That was the first time I'd heard about it. And by that time, MLB had already started to work with these historians to try and right that wrong. But most of us, unless you were really a hard-core student of this game, didn't even know about that commission.

It took me by surprise. Honestly, I wondered if I was just me, and maybe I was tuned out.

It wasn't just you — maybe it was just you and I [laughing]. Maybe everybody else knew.

The recent steps by MLB and Baseball Reference apply to the era from 1920 to 1948, when more than 3,400 players were in the Negro Leagues. What were their careers like? Did they play only during a season, or was this more like a full-time job?

The league structure was mirrored right after Major League Baseball. So they had a dedicated season, they just didn't play as many games. Again, access to stadiums was always a critical part of why things were so challenging for Negro Leagues to survive before Rube Foster formed the Negro National League.

Very few Negro League teams had their own stadiums. They were dependent on major league teams to get access to their facilities, which means they had to wait until the teams weren't playing, or on the road, to get access to those stadiums.

The superstar Negro Leaguers would play all year round. They would go to Latin America in the winter, just like many major leaguers did, to supplement their income and play the game. So they could make a pretty decent living, but they had to play the game year-round.

You've worked for years to gain fair recognition for Negro Leagues players. Baseball Reference announced their change in policy on your birthday — what was that like for you?

Oh, it's been amazing. I take great pride, because I do think the work we've done over three decades here at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum played a role in helping us get to that historic announcement that took place in December, and then led to Baseball Reference expanding their look at the Negro Leagues.

The fact that people are now taking greater notice of the Negro Leagues and its history is very significant and very meaningful. You know, people are celebrating this. It was long overdue, but it's happened. And the players that are still with us, the families of players who have been long gone, this meant something to them as well.

The Negro League players themselves were never seeking validation from anyone, they didn't need to be validated. They knew how good they were, they knew how good their league was. And quite frankly, the major leaguers knew how good they were.

But what Major League Baseball has done, it has paid rightful tribute, and to some degree, it is an atonement.

What about the timing of these changes, especially with where our country is right now?

Timing is everything. As we were celebrating 100 years of the Negro Leagues last year, the social and civil unrest that we saw in our country perhaps sped up this process with baseball. Because I think it was part of an effort to help heal, and baseball has always been at the forefront of social change in this country. It was only fitting that they would be part of the healing process.

I don't know definitively that that had an impact on the timing of this announcement, but I do think both of those things played a role.

If the winning spirit of the Negro Leagues can help us bridge the racial divide that seemingly was growing wider in our country, then it's just another example of the profoundness of this history, and how important this museum is as the caretaker of that history.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.