A new environmental education facility opened to the public in Palatka last month, inviting school groups to learn about wetlands and wildlife.

Some scientists who helped develop the center are questioning whether the manufacturer Georgia-Pacific had too much influence over its curriculum.

The St. Johns River Center has exhibits about the environmental importance of the river and its connection to history and culture of Northeast Florida.

City of Palatka spokeswoman Mandi Tucker says the center’s main purpose is educating children.

“Small youth groups will be able to come in,” Tucker said. “We’ll do special lessons in connection with the Florida state curriculum that’s been developed for us.”

The new center is located on the St. Johns River in the heart of downtown Palatka. It was paid for by Georgia-Pacific, a pulp and paper subsidiary of Koch Industries. A few years back, when the company created a pipeline that dumps waste into the river, the state of Florida required Georgia-Pacific to offset the negative environmental effects.

Jim Maher, with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, reviewed the company’s offset proposal.

“The original proposal went above and beyond, and that was without the wetland center,” Maher said.

But Georgia-Pacific funded the center anyway as a gesture of goodwill, and it brought together advisors to look at its curriculum. Georgia-Pacific spokesman Terry Hadaway says the committee was a diverse group.

“They included environmentalists, they included historians, they included members of the education community watching and guiding us as we put together every element of the center,” Hadaway said.

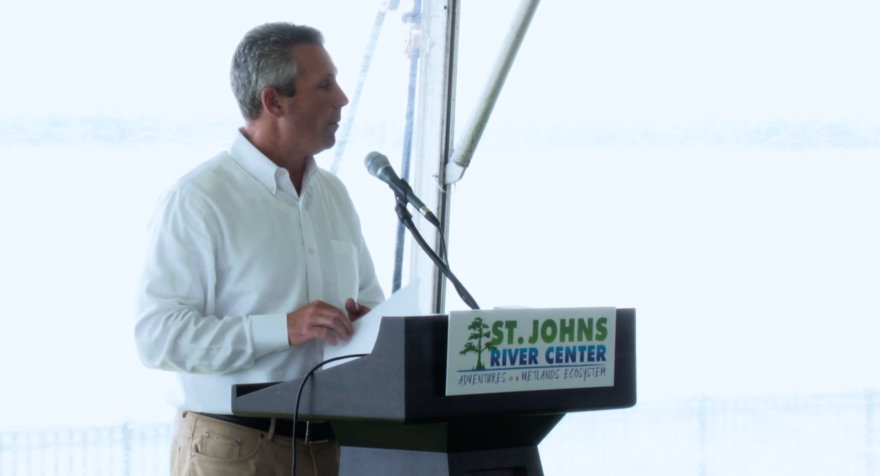

Georgia-Pacific CEO James Hannan spoke at the ribbon cutting in July, saying, “This curriculum is at the core of this center and what makes it exceptional.”

But some scientists on the advisory board didn’t see eye-to-eye with Georgia-Pacific while vetting the curriculum back in 2013. Lauren Watkins, who worked for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection at the time, says she resigned as a St. Johns River center advisor after Georgia-Pacific presented an outline of the curriculum at its first meeting.

Watkins says Georgia-Pacific refused to include key pieces like threats from climate change and sea level rise.

“I was under the assumption that we would be integral in the development of the curriculum,” Watkins said, “and we really thought we were going to be able to contribute to the content, and when we realized that the content was not only already in motion, if not already completed, it was also inflexible.”

Watkins says Georgia-Pacific refused to include key pieces like threats from climate change and sea-level rise.

Another former advisor, Florida Atlantic University researcher Robert Virnstein, says the written curriculum calls for teachers to discuss the benefits of manufacturing alongside units on wetlands and rivers.

Virnstein said, “I guess in terms of the impact of manufacturing, I mean — it’s as if they can coexist or do coexist — but not all is well.”

Georgia-Pacific's Hadaway didn’t respond to several requests for a follow-up interview before this story’s deadline. But in a 2013 email to Virnstein, Hadaway wrote he disputes climate change is influenced by humans. He also said the company doesn’t have an official policy on sea-level rise.

Virnstein says, despite the curriculum’s omissions, he still considers the center a good thing for the region overall.

“I think it’s a huge asset and I think that its value will come in bringing kids to the center,” Virnstein said. “But I think the curriculum will need to change — in fact, it will change — over time.”

Georgia-Pacific’s parent company, Koch Industries, has a history of running afoul of environmental-protection regulations. The EPA fined it $30 million in the year 2000 for oil spills.