Before the phrase “civil rights movement” had even entered the American lexicon, Asa Philip Randolph was among the earliest forces propelling it.

Randolph was born in 1889 Crescent City, Fla. He died 90 years later in New York.

But it was Jacksonville where the man known to many of his peers as the father of the modern civil rights movement would spend his formative years.

The son of an African Methodist Episcopal minister, Randolph grew up in Jacksonville’s Eastside. It was years before he organized the nation’s first black trade union, years before politicians declared him the most dangerous man in America and years before he orchestrated the 1963 March on Washington, where another voice of the movement — a young, charismatic minister from Atlanta — would famously utter “I Have a Dream.”

A widespread understanding of Randolph’s pivotal role in the civil rights movement has been somewhat lost through the years, says University of North Florida historian Alan Bliss.

“We historians, we Americans, we people who celebrate the history sadly overlook the long reach and the powerful force of Asa Philip Randolph in the civil rights movement,” said Bliss. “In the movement for social justice, he argued that all Americans really belonged with the movement for social justice and social equity he argued that all Americans really belonged with the movement for social justice and social equity.”

In the years that followed Randolph’s move to New York in 1911, he came a champion for the working-class man.

In 1917, he co-founded the black socialist magazine The Messenger. By 1925, he established the Brotherhood of the Car Porters at a time when unions were largely discriminatory. The predominantly black trade union won its first major contract with the Pullman Company in 1937.

“He thought that there ought to be working class solidarity in the American political economy and it should transcend race,” Bliss said.

In the years to come, Randolph would put the pressure on Washington’s highest office to take action against workplace and armed forces discrimination. He threatened three presidents with massive demonstrations at their doorstep. The threats were enough to prompt both Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman to sign executive orders banning discrimination in the defense industries, the federal bureaus and eventually the armed forces.

But in 1963, that much-feared march — the March of Washington for Jobs and Freedom — finally took place with more than 200,000 demonstrators and Randolph at the helm.

“Let the nation and the world know the meaning of our numbers,” he told the crowds at the Lincoln Memorial

Randolph’s characteristically quiet dignity and steady resolve left a lasting impression with other young locals who would eventually pick up the torch. A 16-year-old Rodney Hurst was among them.

“The dignity that he carried and the dignity that he showed. You knew that you would follow him anywhere,” Hurst said.

The local civil rights activist and author remembers his own encounter with Randolph a the age of 16, as leader of Jacksonville’s Youth Council NAACP.

“A. Philip Randolph was talking about encouragement, he was talking about keeping the fight going and staying in the struggle and understanding what the fight was all about,” he said.

Hurst would continue that fight along with other Jacksonville youth through sit-ins, demonstrations and an infamous restaurant confrontation with whites known as Ax Handle Sunday. He later chronicled it in his book, It Was Never About a Hotdog and a Coke.

And though Randolph moved away decades before, his legacy lives on Jacksonville. Through a school, a park, a street and most recently an honorary degree.

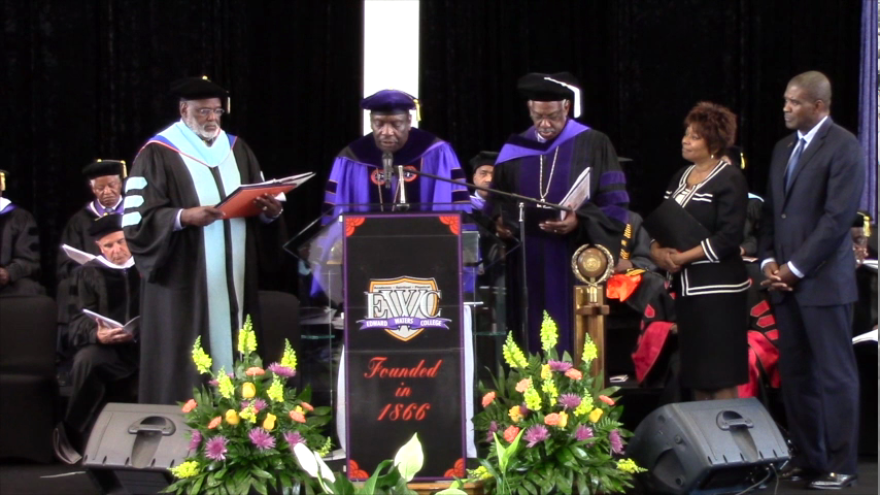

In May he was honored posthumously as an alumni of Edward Waters College, where he attended from age 14 to 16.

Vice President of Academic Affairs Marvin Grant was among the presenters of the honorary degree which went to the Washington-based A. Philip Randolph Institute.

“We’re very proud to let people know this is where he came from,” Grant said. “These are his roots.”

And in a more perfect world, there would be an even more perfect way to honor the late Randolph, says historian Alan Bliss.

“I’d say this about everyone who thinks back about A. Philip Randolph. If we lived in a more perfect and fair world, then Martin Luther King would have lived to be an old, old man and we would celebrate A. Philip Randolph Day.”

You can follow Rhema Thompson on Twitter @RhemaThompson.