In the days after Hurricane Irma tore up the center of Florida in September 2017, 14 residents at a South Florida nursing home died after the facility lost power to its air-conditioning system.

During that time temperatures in the Hollywood area ranged from lows around 80 to highs near 90 with a peak heat index of 99 degrees, which the National Weather Service says is dangerous for the elderly.

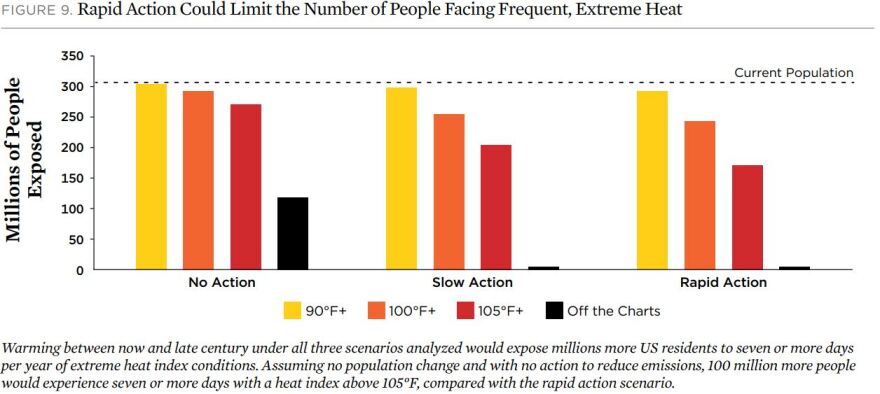

But those temperatures — and higher — are projected to become more of the norm, according to a new report from the Union of Concerned Scientists. Climate change will lead to a sharp increase in the number and intensity of extremely hot days in Northeast Florida and elsewhere unless drastic global action is taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the report concludes.

Related: After Deaths During Hurricane Irma, Florida Requiring Changes For Nursing Homes

Global temperatures have been rising for decades due to increases in fossil fuel emissions, which become trapped in earth’s atmosphere. The planet just had its hottest June on record and July is on track to break records too.

Heat has been the leading weather-related cause of death in the U.S. for the past 30 years, according to the NWS. Between 1999 and 2010 extreme heat was linked to 7,415 deaths in the U.S., an average of more than 600 per year.

Heat is more harmful to human health when humidity is high.

Sweat cools the body when it evaporates. But humidity in the air limits that evaporation, reducing its cooling effect and causing the body to accumulate heat. That’s why the NWS combines temperature and relative humidity to calculate the heat index, or “feels like” temperatures.

“Our analysis shows a hotter future that’s hard to imagine today,” said Kristina Dahl, senior climate scientist at UCS and co-author of the report. “By the end of the century, with no action to reduce global emissions, parts of Florida and Texas would experience the equivalent of at least five months per year on average when the ‘feels like’ temperature exceeds 100 degrees Fahrenheit, with most of these days even surpassing 105 degrees.”

Among all U.S. states, Florida is projected to experience among the most frequent extreme heat.

“At the end of last century, Jacksonville would see an average of about 16 days with a heat index above 100 degrees,” said Astrid Caldas, senior climate scientist at UCS and report co-author. “By midcentury, [in about 30 years], if we take no action to reduce emissions, that number would more than quadruple to over 80. And by the end of the century, it would be about 120 days with heat indices above 100 degrees.”

“On some days, conditions would be so extreme that they exceed the upper limit of the National Weather Service heat-index scale and a heat index would be incalculable,” Dahl said. “Such conditions could pose unprecedented health risks.”

The only place in the contiguous U.S. that historically sees “off-the-chart” days in an average year is in the Sonoran Desert. If no action is taken to reduce emissions, Jacksonville, which currently sees none, could experience two “off-the-chart” heat days by midcentury and 12 by the end of the century, when babies born today would be nearly 80.

“We have little to no experience with ‘off-the-charts’ heat in the U.S.,” said Erika Spanger-Siegfried, lead climate analyst at UCS and report co-author. “These conditions occur at or above a heat index of 127 degrees, depending on temperature and humidity. Exposure to conditions in that range makes it difficult for human bodies to cool themselves and could be deadly.”

Fewer than 2,000 people in the U.S. have been exposed to a week or more of these conditions in an average year. By late century more than 118 million people, or over one-third of the nation’s population could experience “off-the-charts” heat once per year or more if emissions aren’t quickly and sharply reduced.

“The rise in days with extreme heat will change life as we know it nationwide, but with significant regional differences,” said Rachel Licker, senior climate scientist at UCS and report co-author. “For example, in some regions currently unaccustomed to extreme heat — those such as the upper Midwest, Northeast and Northwest — the ability of people and infrastructure to cope with it is woefully inadequate. At the same time, people in states already experiencing extreme heat — including in the Southeast, Southern Great Plains and Southwest — have not seen heat like this.”

“By late century, they may have to significantly alter ways of life to deal with the equivalent of up to five months a year with a heat index above — often way above — 105 degrees,” she went on to say. “We don’t know what people would be able and willing to endure, but such heat could certainly drive large-scale relocation of residents toward cooler regions.”

The report notes that people who work outdoors would face greater challenges than most. Construction workers currently account for about one third of all occupational-heat related deaths and illnesses.

“By the end of the century, on most days between April and October, construction workers in parts of Florida won’t be able to safely work outside during the day because the heat index would exceed 100 degrees,” said Dahl. “Likewise, agricultural centers such as Illinois and California’s Central Valley could struggle to keep farm workers safe, with the heat index exceeding 90 degrees and 100 degrees, respectively, for the equivalent of about three months a year.”

Related: Increasing Number Of Hot Days Threatens Health Of Florida’s Outdoor Workers

Rural areas in the South have some of the nation’s highest heat-related hospitalization and death rates, largely due to how many people work in the farming and construction industries. But cities have to deal with what’s referred to as the heat island effect. Cities tend to be hotter than surrounding areas because they have fewer shade-providing trees and a lot of heat-retaining materials and surfaces like asphalt. And extra heat that’s absorbed during the day is re-radiated at night, keeping air temperatures in urban areas 22 degrees warmer than surrounding areas, on average.

Even within a specific location, vulnerability to extreme heat isn’t equally distributed.

“Low-income communities, communities of color and other vulnerable populations may be particularly at risk when exposed to extreme heat,” said Juan Declet-Barreto, climate scientist at UCS and report co-author. “Long standing social and economic inequities have led to these communities’ often having more limited access to transportation, cooling centers, and health care, and they may lack air conditioning, or the financial resources to run it.”

More than 700 people died during the 1995 heat wave in Chicago, many of them isolated elderly African Americans in non-air conditioned apartments.

On top of the health risks, this extreme heat can increase the likelihood and severity of droughts and wildfires, harm ecosystems, cause crops to fail and reduce the reliability of infrastructure.

But the report states this future isn’t inevitable.

“The best ways to avoid the worst impacts of an overheated future are to enact policies that rapidly reduce global warming emissions and to help communities prepare for the extreme heat that is already inevitable,” Caldas said.

“To ensure a safe future, elected officials urgently need to transform our existing climate and energy policies,” said Rachel Cleetus, lead economist and policy director at UCS and report co-author. “Economists have advised putting a price on carbon emissions to properly account for damages from the fossil-fuel-based economy and signal intentions to protect the environment.”

“Extreme heat is one of the climate change impacts most responsive to emissions reductions, making it possible to limit how extreme our hotter future becomes for today’s children,” said Caldas.

Brendan Rivers can be reached at brivers@wjct.org, 904-358-6396 or on Twitter at @BrendanRivers.