Victoria Gomez waits at a "checkout" table as two volunteers count up her finds: puzzles, felt, storage bins and wooden shelves. "My last [credit] card bill was $1,000 and that's just from last month, just for school supplies and things for my classroom," she tells them.

Gomez is now a kindergarten teacher at The Chatsworth School in Baltimore County. In her two years as a teacher, she has switched grade levels three times.

She came to the Baltimore Teacher Supply Swap for the first time last February, after she was asked to switch from fifth grade to second grade — with one day's notice. Gomez says she panicked — she didn't have any of the materials she needed. She got to the swap warehouse minutes before closing time.

"The people here stayed late. They helped me come up with solutions so that everything worked out, and probably 70 percent of the stuff in my teaching space was from here," Gomez recalls.

The Teacher Supply Swap, a free store for educators in Baltimore, is serving a community with a child poverty rate higher than the national average. Teachers say the Swap and similar organizations across the country are making a real dent in the amount of money they pay every year out of pocket for classroom supplies.

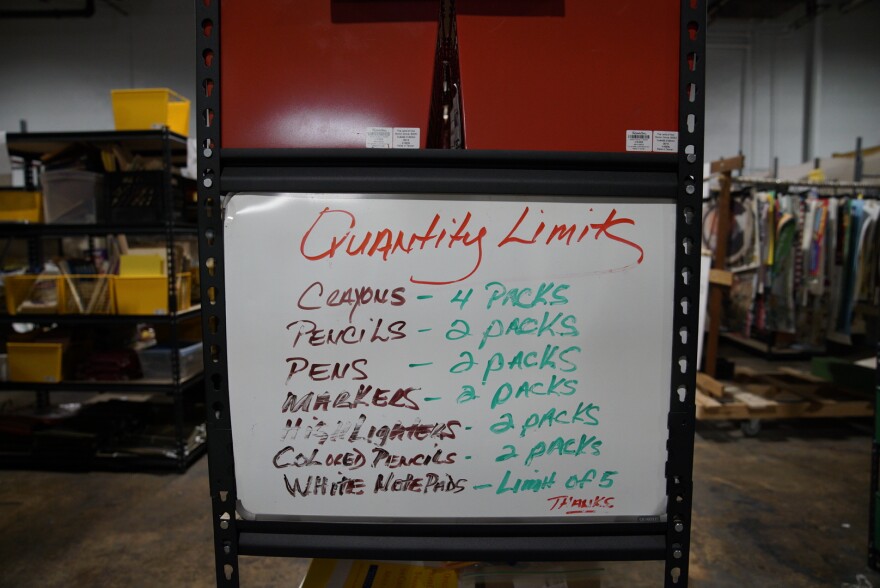

Any child care provider — from home-schooling parents to private school teachers — can shop the Swap twice a week and take up to five tote bags of goods. The first load is free but a yearly membership of $45 gives educators unlimited visits. Last year, the Swap says it gave away more than $127,000 in school supplies. The new or gently used items come from other teachers, local businesses or community members.

On a recent day, the free store bustles with educators. They peruse racks of educational posters and tubs of rulers. A long line of teachers waits for "checkout," the process by which Swap staff can take inventory and tell teachers the monetary value of their hauls.

"You've saved $197 today," a volunteer tells Victoria Gomez.

As Gomez leaves, Paul Veracka enters the free store. He is preparing for his first year as a teacher and just saw his second grade classroom at Calvin M. Rodwell Elementary School for the first time. It's pretty bare, Veracka says, so he came to the Swap with an exhaustive list of supplies.

The Swap had run out of many of the items on his list, but Veracka says he'll be frequenting the warehouse over the course of the school year.

"The Teacher Supply Swap is the only way I'd be able to afford all of this, honestly," Veracka says. "I just got out of grad school and basically have no money, and so all the supplies that I needed [are] just way too much for my salary right now."

He leaves with $44 worth of supplies.

"Teachers aren't exactly rolling in the dough"

Melissa Badeker co-founded the Baltimore Teacher Supply Swap in 2014 as small swap meets among educators at community centers and in church basements.

The meets grew in size, and teachers began leaving materials with Badeker when they couldn't make it. Badeker eventually resigned her job as an elementary school teacher to focus on the Swap full time. It became a free store in 2015.

In 2017, television personality Mike Rowe gave the Swap warehouse a free makeover for his Facebook show Returning the Favor. But Badeker moved the Swap to another warehouse earlier this year because she says the landlord made the space untenable.

Today, the Swap shares a 3,000-square-foot warehouse in northern Baltimore with other educational nonprofits, such as one that gives used sports gear to student athletes and another that distributes secondhand school uniforms.

Other free supply warehouses for educators have cropped up across the country. In Guilford County, N.C., preregistration for the local Education Alliance's Teacher Supply Warehouse fills up weeks in advance. The program, which allows teachers to "shop" using a point system, opens for several days four times each year.

A Nevada school district operates a 6,000-square-foot warehouse for teachers in Reno, which has given away $400,000 in supplies. And a group of Indiana Rotary clubs has run the Teachers Warehouse in Bloomington since 2004.

These programs aim to reduce the amount of money teachers spend out of pocket for school supplies. As NPR reported last year, some estimates suggest that teachers typically spend at least $500 of their own money each year on their students and classrooms. Those costs can skyrocket for teachers of art, science and other disciplines that require specialized equipment.

"Teachers aren't exactly rolling in the dough, so there is a financial burden," Badeker says. "It leads to frustration because teachers are not treated as professionals. Our society is putting our future, our children, into these teachers' hands and we are not giving them the tools to succeed. How can our students succeed if we aren't setting up our teachers to succeed?"

The amount of money allotted to teachers for school supplies varies across the country, and some school districts — like Baltimore City — leave funding to the discretion of individual schools. Per federal law, teachers can deduct $250 each year from their taxes for some out-of-pocket classroom expenses. But to get through the school term, teachers say they must get crafty with their money: clipping coupons, taking advantage of teachers-only discounts at big box stores, and piling up grant applications.

"At the same time, teachers and schools accumulate masses of supplies," Badeker says. "When they switch grade levels, when they retire, when they switch content areas they have supplies they no longer need and ... they want to give it to someone who needs it."

That's why Badeker wants to create a model based on the Baltimore Teacher Supply Swap that can be replicated across the country.

"I envision more Teacher Supply Swaps in more districts in more states," Badeker says. "I hope I can develop a package so that other teachers can take this package and start a location in their own area."

But she admits that the ultimate success of the Swap would be its failure.

"I would love to see us go out of business because we're properly funding our schools and giving our teachers, classrooms and students what they need. But unfortunately we exist because of a lack of funding in education in Baltimore," Badeker says.

"Somebody cares for us"

Until then, the Teacher Supply Swap is ratcheting up its efforts by taking the free store on the road.

Badeker climbs into the cab of an old box truck, donated by a local plumber late last year. She calls the colorful vehicle the Supply Mobile. Its teal exterior, hand-painted by area art teachers, features cartoonish images of scissors, a ruler and glue. The inside of the truck is outfitted with rows of wire shelving that hold plastic bins of school supplies.

Badeker pulls the truck into the driveway of Dayspring Head Start, a summer educational program for young children. She and another staff member unhinge the supply bins from their protective tarps and bungee cords, revealing piles of boxed crayons, bundles of unsharpened pencils and stacks of composition books.

On the sidewalk outside, they set out large storage tubs containing educational posters, bulletin board borders and organizational tools. Badeker fastens temporary metal steps to the back of the truck and borrows a squat, kid-sized table from inside the school as a makeshift checkout counter.

Soon, teachers begin to trickle out of the building in twos and threes. They grab complimentary tote bags and start shopping the truck. Ulrica Crawley, a preschool teacher, tests out staplers.

"This is awesome," she says. "Staplers are always handy."

Crawley chooses a bundle of 10 pencils. She says they might last three weeks in her classroom.

Consumables are always in demand at the Swap — pencils, notebooks and markers have short lifespans in classrooms, especially in Baltimore where nearly 33 percent of children live below the poverty line and often can't afford supplies of their own.

Behind Crawley, another teacher is sifting through pens. "Our parents always take them," she laments.

Crawley makes her way to the bin of posters outside the truck. "This is awesome. I see something! I don't know what I see, but I see something," she says.

Crawley pulls out a string of big, colorful paper letters that spell out "MARDI GRAS." She can use the decoration for her required lesson on cultures of the world, Crawley says, or maybe she will pull it apart and turn it into something new.

"I go overboard," Crawley says of supplying and decorating her classroom. She estimates she spends upwards of $200 on it each year. Today, Crawley will walk away with $56 in supplies from the Supply Mobile — saving her over one-fourth of her yearly budget.

She is happy about her haul, but Crawley says the thought behind the Supply Swap means the most.

"It's a pick-me-up to let us know that somebody cares for us as much as we care for our children," she says.

Between the warehouse and the truck on this day, the Baltimore Teacher Supply Swap gives away more than $6,000 in school supplies to 54 local educators. The following weekend — and for the rest of the school year — they'll do it all over again.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.