One of America's most recent espionage cases started with a friendly hello over the Internet.

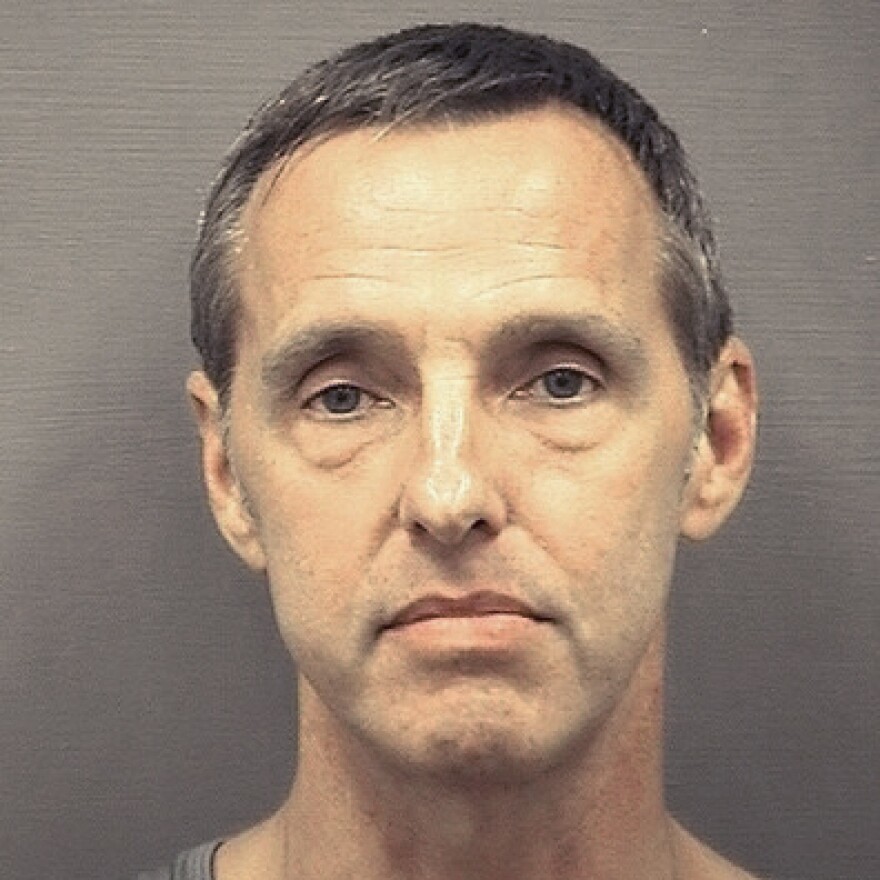

It ended with a jury in Virginia finding former CIA officer Kevin Mallory guilty of spying for China. The Mallory case — a rare counterintelligence investigation to go to trial — provides a lesson in how Chinese spies use social media to try to recruit or co-opt Americans.

For the head of the Justice Department's National Security Division, John Demers, it also highlights a broader point.

"The Chinese," Demers told NPR, "are our No. 1 intelligence threat."

Three former U.S. intelligence officers were convicted of or pleaded guilty to spying for China over a recent 11-month span. Over that same period, the Justice Department brought almost a dozen more China-related cases, most of them for alleged economic espionage.

Demers took over leadership of the National Security Division in February 2018 after being confirmed by the Senate. Since taking the helm, he has spent a considerable amount of time on China and what he calls its prolific espionage efforts against the United States.

They're vast in scale, he said, and they span the spectrum from traditional espionage targeting government secrets to economic espionage going after intellectual property and American trade secrets.

"We had, last year, three traditional espionage cases all involving ex-intelligence community officers going at the same time — that's unprecedented," Demers said.

One of those cases was Mallory, who was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison. The other two cases involved former Defense Intelligence Agency officer Ron Hansen and former CIA officer Jerry Chun Shing Lee, both of whom pleaded guilty.

But there's more beneath the surface that the public doesn't see, Demers said. Take the three former intelligence officers' cases as a starting point, he said, and expand from there.

There are other investigations the Justice Department is running that haven't resulted in charges yet, he said — and then there are the Chinese spies who are operating whom the U.S. doesn't know about.

"Then you go back out and you realize how many Americans you need to approach before you can convince one American to turn on his or her country," Demers said. "That number? I don't know what it is exactly — but it's significantly high."

The Ministry of State Security wants to connect

Demers described a pattern that has emerged in the way Chinese intelligence officers try to recruit Americans.

It's risky for them to operate inside the United States — where they could be interdicted by the FBI — so instead they often initiate contact over the Internet via LinkedIn or other social media.

"That's not unusual," Demers said. "We see the Chinese intelligence officers using social media platforms to reach out to people."

China's spies aren't reaching out willy-nilly. They do their research online to identify the information they want and the people who might have access to it.

And LinkedIn users, often trolling for new jobs, openly advertise their status as employees or former employees of agencies of interest — with access to material that the Chinese want.

Once recruiters find someone who seems like a good candidate, they initiate contact — albeit often with a light-handed approach.

"Obviously, they don't say, 'Hey, I'm from the Chinese intelligence services and I want to talk to you,' " Demers said.

Instead, the Chinese intelligence officers often pose as an academic interested in someone's work or a businessperson who has an exciting job opportunity. Using that cover story, the Chinese officers try to lure the target into visiting China — with all expenses paid.

"And slowly, they start to try to get information from this person," Demers said.

In some instances, Chinese intelligence then sustains contact with its operatives away from LinkedIn or public social media by using clandestine or encrypted communications. In Mallory's case, he received a specially outfitted Samsung Galaxy smartphone, according to court records.

It's a play that has also been used to target folks in the business world and academia, where China is hungry for cutting-edge technology and trade secrets. For years, the Chinese intelligence services have hacked into U.S. companies and made off with intellectual property.

Now, U.S. officials say China's spies are increasingly turning to what is known as "nontraditional collectors" — students, researchers and business insiders — to scoop up secrets.

In two recent cases, the Chinese were allegedly going after jet engine technology and the formula to produce a nontoxic lining for food cans.

Does it all add up to profiling?

The Justice Department's heavy focus on China has prompted some lawmakers and members of the Chinese American community to worry about racial profiling by law enforcement.

Demers said it's a fair concern to raise, but he said the Justice Department's focus is "suspicious behavior."

"We don't start with somebody's ethnicity or their nationality when we start doing an investigation," he said. "We're looking at suspicious behavior, and we're looking at the behavior of the Chinese government."

He added that the Chinese government frequently targets for recruitment Chinese nationals in the United States as well as Chinese Americans, which is why there are many economic espionage cases that involved Chinese nationals.

But Demers also pointed to the recent cases against the three former U.S. intelligence officers. Two of them are not of Chinese heritage.

"It's very clear to us that loyalty knows no ethnic boundaries," he said.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.