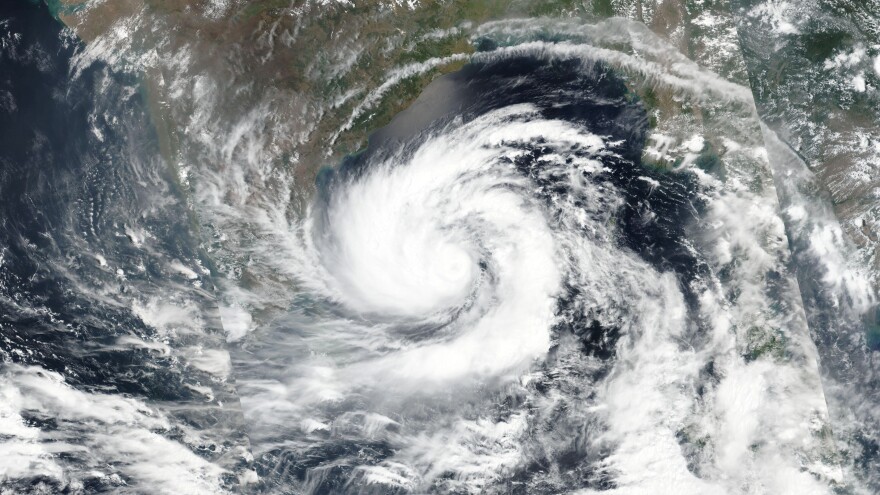

Already grappling with effects of a global pandemic, South Asia is now confronting another major cause for concern: Cyclone Amphan, a storm of historic scale, is churning over the Bay of Bengal and about to bear down on the coastal regions bordering Bangladesh and India.

The India Meteorological Department, or IMD, briefly classified Amphan as a super cyclonic storm — the department's highest storm classification, on par with a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale. Though the IMD says the storm has diminished in strength over the past day — to something more on the order of a Category 4 designation — with sustained winds surpassing 130 mph, Amphan remains the strongest cyclone seen in the Bay of Bengal in more than two decades.

"It will cause extensive large scale damage," as the agency put it plainly.

Meteorologists expect the storm to make landfall on Wednesday local time, along the coast of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal. It's likely to bring a storm surge of up to 16 feet, with the potential to inundate low-lying areas.

While no time is ideal for a life-threatening storm, Amphan is arriving at a particularly dangerous moment for both countries, which are already coping with a catastrophe of an altogether different sort. India has reported more than 100,000 confirmed cases of the coronavirus, while Bangladesh has reported some 25,000. Both countries have responded to the pandemic with extended lockdowns seeking to keep people separate and the virus relatively contained.

All of which presents officials with the all but impossible task of tackling the demands of two catastrophes at once.

"We are facing a dual challenge of 'cyclone in the time of COVID-19,' " Satya Narayan Pradhan, chief of India's National Disaster Response Force, said at a briefing Tuesday. "We are taking action according to the enormity of this challenge."

Emergency officials in India say they have deployed several dozen teams to the states of West Bengal and Odisha, which expect to feel the brunt of the storm. Officials intend to evacuate residents from potentially dangerous structures, such as mud houses with thatched roofs, to more stable shelters set aside for evacuees. Traffic to both states on roads and rail has been diverted or outright suspended, as well.

In Bangladesh, meanwhile, the country's disaster management minister told the BBC and other media outlets that they expect to evacuate about 2 million people from regions sitting in the cyclone's path.

But options are limited. Both countries are already using many makeshift shelters for overflow coronavirus treatment centers, and social distancing measures have meant a significant reduction of capacity in the shelters that remain available. What's more, as The Washington Post has reported, some residents have voiced resistance to the very idea of evacuating and the infection risk it may represent.

It's a quandary that the Philippines struggled with last week when Typhoon Vongfong wrecked coastal areas and left at least one person dead. Countries in the Caribbean are also likely to confront this issue come the start of hurricane season next month.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said he has reviewed the country's response plans with several prominent ministers. "I pray for everyone's safety," he tweeted Monday, "and assure all possible support from the Central Government."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.